This post is a modification of an earlier Sunday Setlist post from May, 2011.

I once had the privilege of leading worship at Holy Family Anglican Church in Hendersonville, TN. It’s a liturgical service that also uses modern worship songs. This is a trend that I’m seeing in liturgical services based on my experience at The Table and St. John’s Anglican Church in Franklin, TN. With the popularity of the “Ancient Future worship” movement, it’s quite possible that more and more of us modern worship leaders will find ourselves facilitating very traditional liturgies at some point, including ancient church music.

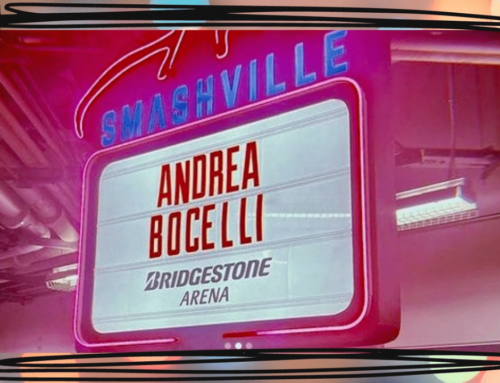

Ancient church music isn’t written in chord charts, number charts, or even classical music notation. For my time at Holy Family, I was given this:

I called my Christian Orthodox friend. He reminded me that any time you see printed music like this, it’s only an attempt to bring an ancient tradition into our system of seeing things. There are a couple of challenges with this notation for those of us who are only familiar with modern music.

Lack of meter and note stems. There is no notation such as 4/4, 3/4, or 6/8. There are no measures per se, but these funny tick marks to indicate a phrase. The notes don’t have stems to clearly define their value. Finally, there is an inconsistency in the number of notes within the phrases. All of this can trip rock n’ roll worship leaders up. This is what you need to know.

- The most important element is the text. This is true of any good worship music, but an especially useful guide here. How would you say the text? That’s a pretty good starting point for the rhythm.

- Darker dots move faster than open circles. Assume they move twice as fast. I also tend to think of the open circles as the “destination” of the phrase. Open circles receive the accents or the downbeat.

- Think of the phrases as “waves” and make everything fit before the next one comes ’round.

- My experience is that grace abounds in the interpretation of the rhythm. However you interpret it, be confident so the congregation can follow

Watch the staff. I missed this the first few times I looked at this music, but note how the staff will sometimes have five lines (the modern custom) and sometimes have four lines. It’s very subtle, but look closely at the third system. I couldn’t figure out the notes for the words “you for your glory.” The notes go off the staff (oh yeah, no ledger lines). So that first note in the third system for the word “we” – it’s not an F# like I thought at first. It’s an A, the same as the last note in the previous system (“you” in “we worship you”).

I once sang in an Episcopal choir that came across music with one or two staff lines. As strange as that seems, at least it’s obvious. It’s easy to miss going from five to four. Here’s what you need to know.

- A clef is not just a symbol slapped across a staff for decoration or to distinguish higher instruments from lower ones. They define where a note is on the staff. (Ask any violists who has to read in multiple clefs). The curl on the

treble clef identifies the note G (the treble clef is uncommonly referred to as the G-clef). Look again at the third system of the Gloria piece.

The clef tells us the first line is G, making the space above it an A.

- However, I think it’s easier to look at the key signature than the curl of the clef. I know that the two sharps are F# and C#. If the second space is C#, the note below must be a B, the space below that must be an A. Of course, if the key had no sharps or flats, I couldn’t rely on this method, but it is how I figured it out in this case.

There. Now you can say you learned something today.

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Read my comment policy.

4 – line music staffs? A Lesson In Music Notation http://t.co/4NhJnCUvMt

Yep. I’ve seen as few as one line, I think.